Rethinking the role of technology in Early Childhood Development

.png)

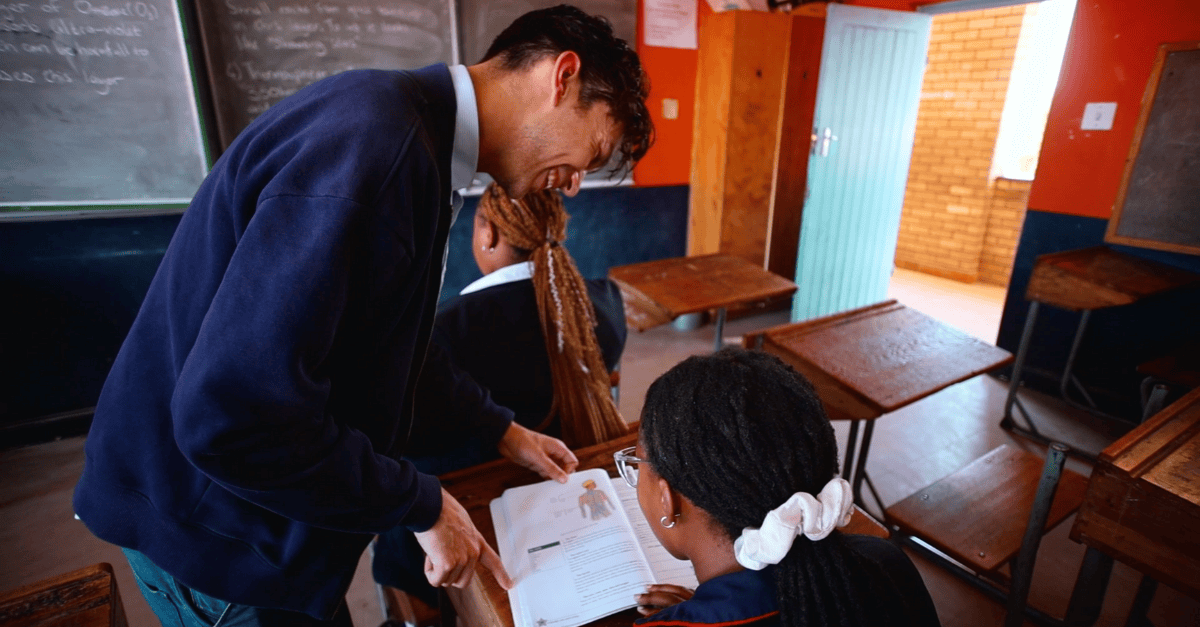

Walk into almost any South African home, crèche, or primary school today, and you’re likely to encounter a familiar sight: a young child confidently swiping through a tablet, tapping their way through an app, or streaming a video with ease. Digital devices have become a natural part of childhood and with that comes both exciting opportunities and pressing questions about how technology shapes learning, play, and development in these formative years.

It’s evident that technology has become inseparable from the lives of our youngest citizens. South Africa is a country where access to quality Early Childhood Development (ECD) is a challenge, as there are still ongoing and robust debates about whether technology is a powerful enabler of access, or a hidden threat to the social, emotional, and cognitive growth that underpins a child’s future.

Injini believes that technology is not the enemy of development, but it cannot be the sole architect of it either. Our team recently attended the Early Learning & Foundation Phase Conference 2025, and from panel discussions that took place, it was clear that technology’s role in early learning must be deliberate, balanced, and contextually relevant.

The ECD tech debate: Why it’s not all good or all bad

For Katherine Tredinnick, Injini’s Research Lead, balance is key.

Technology can play an important role in improving literacy, boosting parental engagement, or strengthening practitioner capacity, though it’s best for this technology to be kept behind the scenes, rather than being used directly by the child.

There are real risks of exposing young children to too much screen time. Research has linked screen overexposure in young children to reduced physical activity, heightened anxiety, disrupted sleep, attention difficulties, and an overall detriment to optimal child development. As Tredinnick cautions, “screens cannot replace face-to-face interaction and play, which are critical for a child’s development.”

The National Department of Health, echoing the World Health Organisation’s guidance, recommends no screen time for children under two, and a maximum of one hour per day of high-quality, supervised content for children aged two to five. These limits remind us that digital experiences should complement and not replace physical play, storytelling, and peer interaction.

There are a number of initiatives in the early learning sector in South Africa that use technology in responsible and impactful ways. For example, Grow ECD provides digital support to principals and practitioners on administration, training, and activity ideas while keeping the classroom itself focused on play-based learning. Bamba Learn sets screen time limits offering short, engaging lessons that support the work of early learning practitioners without exposing children to too much screen time. Parents, too, can play a proactive role by co-viewing content and setting time limits.

At Injini, we focus on understanding how to maximise the benefits of EdTech and reduce its risks, working with innovators, policymakers, and practitioners to ensure technology strengthens, rather than undermines, the foundations of early learning

Everyday scenarios that matter

The National Department of Health, echoing the World Health Organisation’s guidance, recommends no screen time for children under two, and a maximum of one hour per day of high-quality, supervised content for children aged two to five. These limits remind us that digital experiences should complement and not replace physical play, storytelling, and peer interaction.

In practice, some ECD centres are showing how this blend works. Grow ECD, for example, uses digital platforms to support principals and teachers with administration, training, and activity ideas while keeping the classroom itself focused on play-based learning. Parents, too, can play a proactive role by co-viewing content and setting limits.

The power of mother tongue in early learning

Kumbula Xego, Injini’s Senior MEL Associate, believes that language is another critical layer to this conversation.

“The ECD conference reinforced what research has shown us for years, that home language is fundamental to a child’s ability to read for meaning,” she reflected. PIRLS 2021 results revealed that most South African children struggle to read in any language, including their mother tongue. The problem, Xego noted, begins early: “Vocabulary is built at home. If children are not exposed to rich, varied language in their mother tongue, their reading foundation is weakened.”

EdTech has the power to bridge language literacy gaps by providing tools that support bilingual learning and language acquisition. Companies like Ambani Africa, Limu Lab, and EduFeArn are already creating high-quality and culturally relevant content.

“When children understand the world around them in their own language, they gain confidence and cultural grounding. Those concepts later transfer into English or other languages, but their roots must first be strong.”

However, Xego also rightly noted that there are high costs for resources required to produce pedagogically sound content in all 12 official languages. This is a resource-intensive task requiring skilled teams of developers, linguists, learning designers, and illustrators.

A responsible path forward

The path forward requires collaboration, capacity building, and a collective rethinking of what ‘quality learning’ for South Africa’s youngest citizens really means. This includes greater investment in African language content, ongoing research into screen time impacts, and policy frameworks that embed balance into our classrooms and homes.

Injini believes the goal is not to raise “digital natives,” but well-rounded children who are curious, resilient, and rooted in their identities. Technology, when used responsibly, can be a powerful ally in that journey, but it must always remain just that and an ally, not the architect.

.png)